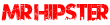

Why are people allowed to be despicable in wartime? Why are all of man’s base desires and impulses laid bare when society has cracked and broken? What happens to human nature? What happens to our souls? At the heart of Amis’ unusual novel is the question of what we turn into when stripped of all our human dignity and what happens when polite society turns back into the wild kingdom and the rules of decorum are pretty much tossed.

Set mostly in a Russian Gulag during the height of the Stalin’s crackdown on dissidents, politicals and anybody else he chose to persecute, our protagonist is turned from a war hero into a fascist criminal by the Soviet system and thrown into a work camp. Truth be told, the camps were less like jail and more like slavery. How else to conscript those in a communist country to do the state’s undesirable jobs (which profit the state)? Our main character, who remains unnamed throughout, was imprisoned despite his past glory. Although, as the story unfolds, we find out that his glory includes raping and pillaging and more raping. In every way he is a war criminal, but it’s not these crimes that go punished, but imaginary crimes against the state that in some karmic way at least makes up for something somewhere.

Thrown into the mix is a love triangle with a Jewish woman named Zoya, and our protagonist’s half-brother, Lev. While our main character is in the gulag, his brother, a pacifist poet, strikes up a relationship with Zoya, a woman they both knew and pined after on the outside. Lev eventually ends up in the same camp as his brother (as all good poets do), and breaks the news to him that he and Zoya are an item. Our main character, being the brutish man that he is, can’t believe that Zoya would go for his homely, wimpy bother. And it’s not until she shows up for a conjugal visit in the House of Meetings that the reality hits home.

Ultimately neither character can escape his past. But to the thug, the camps are but a continuation of a violent and brutish existence, but to the passive poet, it is a life-changing ordeal that pushes his understanding of cruelty. Broken and dispirited, Lev, who should have the life every man wants, spirals into the abyss. His unnamed brother emerges from the camps as the same unapologetic monster that he was when he went in. Did the war and the camp change his nature, or would he have been this person regardless?

I feel like I was right on the verge of really getting this book, but it seemed to slip through my fingers. It’s just so atypical of Amis that I have a hard time connecting it to him, but I guess every book can’t be about drunken, dart-throwing louts.